About the project „Wiener Video Rekorder“

Gabriele Fröschl

Relatively cheap video cameras, which became widely available from the 1980s, turned private filming into a mass phenomenon: the family at Christmas, on vacation, taking a walk, children growing up, pets, living space in the city, the workplace, events in public places. Over the years a treasure of private video recordings has emerged, which would also be of great importance to the scientific analyses of researchers from various fields. Unfortunately, these private recordings – in miscellaneous now obsolete video formats – have never made their way into a public archive so far and await their impending end in their creators' apartments. Many know this problem from their own experience: tape jam, video tapes become unplayable, playback devices break and are no longer commercially available. Once these recordings are no longer accessible, the material saved on them is also irretrievably lost, as videocassettes often represent the only preserved copy in these cases.

For the area of private video documents, this Vienna-centred collection constitutes a unique collection, which permits future research projects relevant insight into Vienna's private spaces, with the archive functioning as a hinge between the private sphere and the public space. As there are mostly video recordings from people living in Vienna, a picture of urban society over the years is outlined, in which societal transformations and social movements are reflected in the same way as technological change in the use of information technology.

Collection

The starting point of this research project was the fact that in most public archives the private space is hardly or not at all documented. Here, a gap arises between that which privately exists and that which is preserved in public archives. Private video-documents – be it documentations of private (often family) events or private documentations of public events or the public space – are potentially relevant sources for archives that provide another aspect of tradition and represent valuable additions to published sources and released sources (such as radio or TV recordings). The aim of the project, therefore, was to assemble a collection of private video recordings - i.e. recordings created in a private context that had not previously been released - beginning in the 1980s, document them, preserve them for the long term and make them accessible.

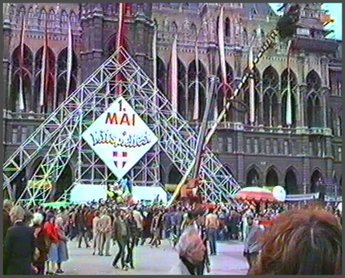

Promotion Uni Wien. Zeremonie

Collection matrix: Milestones: Graduation at the University of Vienna

Collection matrix: Milestones: Graduation at the University of Vienna

The project's focus on video results from the technical properties of the formats: they were prevalent during the time period from the 1980s to the turn of the millennium, especially in the consumer sector, yet their preservation perspective is a very bad one, thus posing the threat of irretrievably losing a specific type of source that can only be minimised by a consistent collection and preservation strategy. Collection building in audio-visual archives is a genuine scientific practice of basic research. Current and future scientific research depends on a consistent collection in this area, since audio-visual archives in Austria are not based in a dépôt légal regulation, thus the collections have to be based on an active collection strategy.

Closely connected to the collection strategy in audio-visual archives is the strategy for collection preservation: digitisation and digital long-term archiving. The time frame available for transfer into a digital long-term archive is limited. Questions concerning threats to the formats as well as availability of playback devices are essential for a collection strategy - to guarantee that private video documentations do not become archival residues as museum carriers without readable content. The future options of private video recordings are as follows:

- Analogue / digital media, which were digitised in time and are available as digital copies after the carrier's and/or playback device's lifespan ends, thereby preserving the essential, namely the recording.

- Analogue / digital media, which were not digitised and are "dead" archival material due to either the deterioration of the carrier or the no longer existing playback device, and constitute residues of the archive or the private collection as museum carriers without readable content.

Considering that audio-visual sources are still seen as mere additional, illustrative material in the humanities and social sciences, it has to be stressed again that actively selecting sources – like the acquisition in this project –, transferring analogue material to digital formats – a multi-layered, complex and scientifically responsible process – as well as making these sources accessible are independent scientific activities, which are prerequisites for further scientific analyses of the material. One of the project's key results – especially because of the source material's properties – is that the source material is only accessible for further scientific research after undergoing these processes.

From this insight resulted a number of tasks that were initiated during this project: In addition to the technical requirements regarding the digitisation of different source material, questions concerning archival collection and publication strategies as well as reflections on the archive as a public space and its self-conception ensued.

Hypothesis

AV-archives portray only part of the public in their collections; with a social and media change sources are created that document significant parts of the public but are not present in archives.

In the course of the project "Wiener Video Rekorder" a collection of a total of around 3.000 private videos from the early 1980s to the 2000s could be assembled.

The now available holdings are to be classified as a closed collection, which was developed under specific circumstances during a limited time period. This collection deigns a look at a particular source type, conveys content that had previously not been available in an archive on such a broad scale – on a national or international level – and in its entirety represents an addition to published and public sources – general statements should however always include the collection's genesis.

These privately produced sources are currently (still) available, but will not survive in their variety due to their properties, which – if it is not actively prevented – will result in a restriction of the recorded image.

The project "Wiener Video Rekorder" has clearly shown that the state of conservation of private holdings is consistently worse than that of comparable media formats from archives, which are stored under climatic conditions suitable for audio-visual media and manipulated according to professional requirements. The time frame for digitisation of video formats is very restricted due to the source's properties and the obsolence of playback devices; this applies especially to recordings from the private domain.

AV-archives define the image of the present for future generations: not everything can be preserved, but the necessary selection should be based on documented strategies.

The project "Wiener Video Rekorder" has shown limits to curating collections from the private domain. Many of the transmitted sources are subject to a certain randomness (but in their entirety nevertheless permit statements) and divers selection processes both on the side of the producers and the archives:

- selection of what is privately recorded

- selection of what is privately preserved

- selection of what is given to an archive

- selection of what the archive includes in the collection

- selection of what is digitised and long-term archived

The selection process on the side of the producers in particular can hardly be affected or documented by archives. What is eventually preserved in an archive is therefore just a segment, which is only in part based on a specific collection strategy.

Furthermore, it has become apparent through the course of the project that the collection strategy in this area is highly dependent on personal contact to producers – an undertaking that can scarcely be incorporated into the daily operations of an archive. Here, specific collection projects (conceivably with different emphases) are needed on a regular basis. For lack of internationally comparable projects a statement about the extent to which the present collection is representative for the source and the time period is only possible to a limited extent. Here, follow-up projects for comparisons would be of interest.

The easy availability of AV-sources owing to publishing strategies by AV-archives prompts the scientific study of this type of source, which is currently still underrepresented compared to the importance these media have for the public.

Due to the online availability of segments from the collection, the barrier for studying these holdings has decreased. Regarding the entire collection it has to be recorded, however, that linking publishing strategy to ethical principles and leaving the decision on the extent of accessibility to the bearers tends to result in restricted access. Here, the desire of researchers (and archives) to find (and make accessible) as much as possible online is opposed to the bearers' wish for preservation of privacy.

Workflow

1. Acquisition:

Strategies regarding collection acquisition focussed on the following points:

- Collection calls through media partners (print media, radio)

- Contacts to relevant associations (e.g. film amateurs)

- Contact with relevant institutions (e.g. district museum, Austrian Film Museum)

- Private contacts

From the start, the project was designed in a way that allowed for the incoming collection to be processed during the course of the project, if at all possible. This is mostly due to the fact that video has a significantly smaller time window for digitisation and playback options than is the case for film (and respective collection projects in the film sector). The conception of a large collection without specific digitisation intent is not constructive for video formats, which is why the collection activities were adjusted for processing. In total, 3.000 video tapes were incorporated into the collection of the Mediathek, 1.953 with an average playtime of 2 hours were digitised. The deviation between digitised and collected video carriers is explained by the fact that not all collected content is classified as private everyday life documentation – and thereby the project's subject. The project has, however, turned out to be an anchor for adding further collections beyond the project's scope, a lasting success exceeding the specific project plan.

An essential part of acquisition was the personal conversations with the bearers. Collecting sources in particular from the private domain has a strong active component: building a collection depends considerably on personal attention to the collectors and on access to specific groups of society. Public calls asking to give these kinds of documents to an archive generally only work well for both parties if intensive support is given. Anonymous transfer options, such as an upload platform, were implemented during the project, but did not produce the expected results and their use has currently been discontinued for that reason. The fact that users upload videos on social networks cannot be utilized for archival projects, as the users' focus in the aforementioned is different, namely to connect and be publicly present. Here, the archives' aspiration to provide a collection for future scientific research and documents of social relevance for future generations is too abstract to be shared by the majority of the bearers. Mostly, additional incentives like a digital copy (which was provided in the present project and probably was a significant incentive) are needed to encourage people to give their holdings to an archive.

The strong personal component of collecting the private also plays a part when attempting to incorporate collections of closed social or political groups or of parts of the population that are underrepresented in the institution compared to the population as a whole, for example of migrants. Missing contacts to a social or political scene hinder the development of corresponding collections or even make it impossible. Here, it has been shown that there are limits to curating such collections.

By being incorporated into the archive's collection, the context assigned to the documents changes. This shift in meaning through the act of archiving is not a phenomenon specific to media archives and does not only affect sources from the private domain. Both the production process and the use in the original context are fundamentally different from the archival source; this process of transformation also takes effect with "home movies": from a private narrative pattern, which hands down family history and, ideally, is an active and regularly received family narration, to a increasingly anonymous example of social practise, which acts as a representative for specific documented facts – an effect that intensifies with temporal distance. The source's increasing anonymisation and the missing context are criticisms sometimes expressed with regard to collection projects. To counteract this, gathering metadata on the collection history and the production process (memories, which were in part fragmentary or inaccurate) as well as future use of the holdings granted to the archive, were a main part of the conversations. The resulting reports are also part of the collection and available for further scientific use of the holdings.

The bearers were free to decide the future use of the holdings in the archive. Audio-visual media are subject to legal restrictions (copyright and related rights – these take effect with released materials in particular) on the one hand, but also – and particularly in the area of private source material – ethical restrictions. The archives' and researchers' efforts to make everything available to the public without restrictions is in conflict with the bearers' wish for controlled access – a wish which was taken into account in this project, as this is seen as part of the ethical obligation public archives have regarding the handling of their holdings. The restrictions do not only affect the video documents themselves but also the secondary sources (which for this reason cannot be made available online at all).

The restriction shows in the following points:

- The majority of the holdings were anonymised at the bearers' request. It was agreed with the bearers if and under which conditions they may be contacted by future users for scientific purposes.

- The online use of the sources is restricted in many cases. The collection, which is available on site in the Mediathek, is not identical to the sources available on the Internet: online there are predominantly segments and the thematic composition of the two pools is not congruent either.

2. Digitisation

Digitisation was the prerequisite for editing the material.

For basic considerations on the subject of video digitisation as well as for specific aspects concerning this project we refer to Marion Jaks' text „Video erhalten! Qualitätsentscheidende Momente in der originalgetreuen Digitalisierung von Video“.

In the course of the project the following video formats were digitised (target format: FFV1 in AVI container):

- Betamax: 31

- BetaSp: 1

- DVD: 67

- MiniDV: 225

- V8/Hi8: 488

- VHS/S-VHS: 917

- VHS-C/S-VHS-C: 222

- Video2000: 2

SUM: 1953

With an average playtime of two hours, the digitised collection of "Wiener Video Rekorder" comprises around 3.900 hours.

Digitisation and the permanent digital long-term archiving were the Österreichische Mediathek's own contribution to this project.

Digitisation in a scientific context requires i.a. detailed logging of each step of the transfer process and includes the responsible minimisation of information loss.

Though there is currently no internationally agreed upon archival format for film/video (in contrast to audio: broadcast wav), in the current discourse the chosen open FFV1 format is well on the way to becoming the international standard for long-term archiving of video, not least due to the efforts of the Österreichische Mediathek within the IASA.

The digitisation of holdings was a prerequisite for further development of the material – working with analogue holdings would have been impossible due to their condition as well as the availability of and demand on playback devices. Here, the challenge to render the source readable again through proper digitisation (see picture before/after) was mastered.

The quality of the collection's individual videos greatly varies and depends above all on format and archiving conditions in the private households. However, three general statements can be made on the type of amateur video – especially in comparison to the type of amateur film:

- Amateur video on average has a considerably longer playtime than amateur film. This is media-related and owed to the technical requirements, but affects the narrative as well.

- Amateur videos are often – from today's standpoint – of "worse" image quality than film. That is not due to the digitisation process or the chosen format for digitisation but to the comparatively worse source format. One aspect of the shift from film to video was that both recording devices and storage media became cheaper and evolved in part in the direction of consumer formats. Affordable equipment, which has led to a democratisation and broadening of recording possibilities, also affects – at least in the early period of video (on which the present project primarily focuses) – the quality.

- The format video makes it possible – also in the amateur sector – to record image and sound. This technical condition permits another dimension of memory: the medium defines the content.

3. Metadata collection

Based on the digital sources, metadata was collected for each recording, as far as it was available or could be deduced from source inspection: personal data (anonymised), place of recording, date of recording, content description, label on the original tape, index, edition details.

For these holdings a collection matrix was created, which is also the entry point to the database query on the website:

- milestones

- feasts and festivities

- partners, family, friends

- public space

- cultural events

- recreation

- activities in the public space

- travel documentations

- migration

- sports

- work; company parties

- private documentations

As metadata collection and development is based on close and potentially repeated viewing of the material, it was very time-consuming and represented a major part of the project.

4. Online platform

Those parts of the collection that were released for publication and complied with ethical criteria are – after consulting samples of the bearers – directly accessible online. Here, additional restrictions regarding privacy were placed by the archive – being conscious that ethical restrictions are always subjective and prevailing taboos are subject to cultural change (to mention the taboo nudity, in particular of children, as an example).

Metadata is available online for all sources of the collection. The entire holdings can be viewed at the Österreichische Mediathek.

How public the private was to become was left for the bearers to decide, the tendency was towards restricted publicity. Many bearers choose anonymity, which permits only limited additional information on the video source. Contextualising material is often not only not available online but due to legal or ethical principles restricted in the archive as well: consent to release holdings to a public archive, consent to research the holdings in the archive, restricting internet access – here the archive is trusted with a "gatekeeper" function, that ensures the holdings are used in the interest of the bearers.

(Published: 2017)